Curator’s Preface and Acknowledgements

In his recent artistic work, Gerry Eskin has been engaged with a diverse range of media and creative forms, primarily focusing on digital photography and ceramic pieces in both sculptural and functional formats. Despite the technical and stylistic variety of the artist’s production, all of his recent pieces have been dedicated to the artistic theme of monumental scale. His expansive photographic panoramas feature vast mountainous desert landscapes in the area of Moab, Utah. The ceramic pieces include outsized painted platters with geometric designs inspired by Anasazi pottery, towering columnar forms and massive anthropomorphic vessels whose shape evokes ancient sarcophagi.

In addition to their audacious scale, Eskin’s works reflect the artist’s preoccupation with the ritual functions and sacred aura associated with ancient cultural objects and landscape sites. In curating the exhibition, the aim was to devise an environmental installation integrating this diverse array of artworks, as well as the conceptual themes of monumentalism and the sacred. As the installation photos document, the photographic landscapes spanning the walls were intended to delineate imagined geographic boundaries within the gallery. The circular configuration of columns forms an architectonic space suggesting a prehistoric monument, creating a sacred zone for the placement of vessels. Inspired by the symbolic connotations of Eskin’s works, this installation scheme represents traditional beliefs in sacred landscapes and their mythical relationship to architectural sanctuaries and forms of burial. For example, in ancient Native American tribal cultures, particularly in the Southwest, mountains were regarded as the abode of gods and ancestral spirits, and in many of these cultures, ceramic vessels frequently were placed in burial sites with the dead, serving a variety of funerary purposes and ritual meanings.

The publishing of this catalogue significantly documents the impressive and dramatic installation of Eskin’s large-scale works at the Figge Art Museum, which stimulated a provocative and unforeseen dialogue between aspects of his varied artistic production. Indeed, the images in this catalogue serve to reveal the crucial role of installation design in more fully conveying the symbolic content of Eskin’s work.

I owe a great deal of thanks to Mark Tade for his masterful photography of Gerry Eskin’s art and his unique ability to capture the important and singular experience of viewing the artist’s work within an installation context. Leanne Paetz’s striking design also greatly enhances the visual presentation of Eskin’s art. I also want to thank Jun Kaneko and Michael Godsil for their informative written statements, which serve to illuminate the aesthetic and technical intricacies of Eskin’s ceramic and photographic practices.

A number of individuals greatly contributed to the successful organization of the exhibition when it was on display at the Figge Art Museum from June 6 through August 29, 2010. I extend my greatest thanks to Gerry Eskin for creating these inspiring works and making them available for display. Sandie Eskin also deserves tremendous thanks for her tireless work in compiling checklist information and helping to coordinate a variety of organizational details in the development of the exhibition. In addition, this exhibition would not have come together without the dedicated assistance of Eskin’s loyal “studio team” in Iowa City and Aspen, Colorado, which includes Ben Upchurch, Evan Evans and Josh Hendricks. I also want to thank Chunghi Choo, Karen Reisetter, and Katherine Grimes and Jeffrey Currie for the generous loan of works from their collections. I also want to extend my gratitude to Rao and Veda Movva for their generous financial sponsorship of the exhibition.

Finally, I want to thank the staff of the Figge Art Museum for their supportive assistance, in particular our registrar, Andrew Wallace, for his invaluable help in compiling checklist information and for coordinating the complex shipping and loan arrangements. I also am very thankful to Courtney Johnson and Andrew Wallace for all of their professional patience and assistance in helping to design and install the complex exhibition.

SCALE: The Landscape Photographs of Gerry Eskin

The title for this exhibition, “SCALE,” references the central challenge that photographers seeking to create images of the expansive landscapes of the desert Southwest have faced from the earliest days of photography. It is a challenge that continues to this day despite the many improvements in photographic equipment, materials and processes during the past 150 years. Most of the earliest photographic images of the desert Southwest were made between the 1860s and 1880s by expeditionary photographers such as William Bell, William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, Andrew Russell, Carlton Watkins and others. In many cases, these photographers were hired to accompany federally funded military expeditions assigned to explore and map the large, uncharted areas of the American Southwest and document its vast natural resources. Each of these early photographers wrestled with the visual challenges of how best to convey the expansive scale of Southwestern landscapes in photographs for their viewers back East. At that time, the technology to “enlarge” negatives to obtain larger prints had not been invented so photographers had to shoot glass-plate negatives the same size as the final prints they desired. The normal glass-plate cameras of the day produced negatives and prints that seemed inadequately small relative to the grand scale of those landscapes. Consequently, several expeditionary photographers chose to address this issue of visual scale by employing an oversize camera, which produced 18” x 22” prints—approximately four times as large as the standard cameras of the day. Even with the larger prints, it still was difficult to sufficiently convey the relative sizes and expansive distances of various landscape elements within the photographs; there rarely were buildings, railroad tracks, telegraph poles or other vestiges of human construction to include as visual guides to reference implied scale. Both Jackson and Russell frequently chose to include one or more human figures in the near foreground or middle ground of their landscape compositions, specifically to provide a reference that would visually establish a sense of scale for their viewers.

The immense distances visible in Southwestern landscapes, coupled with the monolithic dimensions of geologic features such as cliffs, boulders and distant buttes, continue to frustrate and challenge the efforts of contemporary photographers to capture images that provide viewers with an adequate sense of scale. This exhibition of primarily stitched, digital panoramic photographs by Gerry Eskin addresses those challenges of scale head-on. His solutions, while employing modern materials and processes, actually are conceptual extensions of similar attempts by those early expeditionary photographers. In a couple of photographs, Eskin has included human figures in the middle ground of the image, providing us with a visual reference that reveals the expansive scale of the landscape. The modern technologies of digital photography, computer image-editing software and large-dimension photo printers all have been employed to produce stitched panoramic views that measure nearly 2 feet high by 10 feet wide, plus two diptychs that span approximately 20 feet in length.

The end result is a different viewing experience than what we usually expect when approaching a photograph. To appreciate the intricate details within the landscape, one must stand within a few feet of these large panoramic photographs; yet at that distance, it is impossible for the viewer to take in the expansive width of the entire print. When one moves back further to stand approximately 20 feet away, it becomes possible to take in the full width of the panoramic image in a single view; but at that distance all of the intricate details become impossible to see. Thus, the ideal viewing experience for these broad, panoramic prints becomes one of walking past the prints while a few feet away, allowing the image to “unroll” as it reveals itself ahead of you. This is much the same way one would unroll and view a long, continuous Chinese or Japanese scroll painting. This experience could be similar to walking through that actual desert landscape, appreciating all the intricate details and visual surprises. Viewing the large panoramas in that manner also may allow one to experience aspects of the sublime, as one quickly may feel physically small within the expansive scale of the image. In this regard, Eskin’s large panoramic prints hold the possibility of the viewer experiencing something “equivalent” to what a viewer in the physical landscape might perceive.

As for the technical details of these images, all were captured on a Canon 10D digital camera using a tripod with a panoramic head. They were taken during a 10-day period in September 2007, while Eskin was participating in an Anderson Ranch Arts Center master photo workshop in the Moab, Utah, area. The workshop leader was National Geographic photographer David Hiser. Each of Eskin’s 10-foot-wide panoramas was the result of stitching together five to eight individual digital images. The prints were made with an Epson 7600 inkjet printer using archival materials and mounted on Dibond aluminum sign panels.

The prints then were sprayed with several coats of matte fixative to protect the ink. If any of those early, expeditionary photographers could be here today and view this exhibition, they would be envious of these modern solutions to the challenges they faced in attempting to adequately convey a sense of the expansive scale of Southwestern landscapes.

Photography Instructor

Knox College Art Department

Galesburg, Illinois

Gerry Eskin: Time, Place, Intention

Gerry Eskin is a man who possesses a great deal of curiosity.

Curiosity about many things on multiple levels.

He has a keen desire to understand things in depth, like a researcher, yet at the same time, he has the ability to throw all learned knowledge to the wind and create a new path.

He can see big and see small.

This has given him his sense of TIME.

The work referencing itself dances back and forth.

It informs you of the time and place you are in physically and mentally.

Old yet new, these instinctual images ring clear and intentional in their energy.

This gives the work a sense of PLACE.

In all the things that Gerry Eskin creates, there is a basic sense of humanity.

Basic is the most elusive thing to achieve—the most simple essence of emotion is stated in these human-like forms.

Clear about his vision, passionate about his feelings, Gerry Eskin’s instinctual sculptural images speak to us in a universal way.

INTENTION is the life of this artist.

Artist

Omaha, Nebraska

Artist Biography

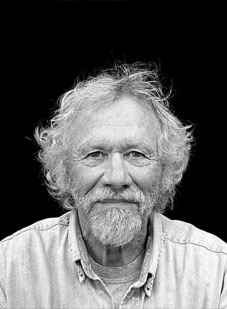

Dr. Gerald Eskin was a studio potter and photographer who maintained studios in Iowa City, Iowa, and Aspen, Colorado. As a ceramicist, he created both functional pottery and sculptural forms. In recent years, he also was engaged in experimental work in digital imaging, returning to photography after a long period of inactivity. Much of his photographic work focused on large-scale panoramic images of expansive landscapes that explore issues of spatial experience and scale.

Eskin was an adjunct professor of studio art and art history at the University of Iowa. His work is included in a number of major collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Arts and Design (formerly the American Craft Museum), Longhouse Reserve, the Mint Museum and the University of Iowa Museum of Art. He also served as chairman of the advisory board of the National Council on Education in the Ceramic Arts, a board member of the American Craft Museum and a member of the advisory board of the University of Iowa Museum of Art. Prior to pursuing his artistic career full-time, Eskin taught marketing and marketing research at Stanford University and the University of Iowa. He received his doctorate in economics at the University of Minnesota. He is a founder and was director of Information Resources, Inc., one of the world’s leading providers of marketing information and related software.